The Immigrant Family Business

By Jacqueline Raposo for the Nov/Dec 2021 issue of Plate Magazine

Read on Plate Magazine.

Click here to Download a PDF of the story for your reader.

The Patel Family of/at Besharam in San Francisco.

When Heena Patel decided to open a restaurant, family involvement was an assumption. For decades, she and her husband, Paresh, had worked 12-hour shifts in their flower shop and liquor store to secure the family’s finances while their children, Vishakha and Ankoor, ate, studied, and played around them. “Nobody else will understand where my drive comes from,” says Heena of pursuing her passion as she approached 50. “It’s just not possible to hire that kind of help.”

The Patels opened Besharam in San Francisco in 2018. There, Heena showcases cuisine from her native Gujarat, India. Paresh manages the front of house. While having unrelated careers, Vishakha and Ankoor jump on the line to make 700 parathas when needed and oversee contracts and communications. “They’re never going to get recognized for the talent I’m using,” Heena says of her children’s contributions. “They’re giving their hearts to me, like I did for them.”

A 2016 National Restaurant Association report shows that immigrant-owned restaurants make up 29 percent of the restaurant and hotel sector, a larger percentage than overall immigrant business ownership. Multi-generational family involvement—with its give and take, built-in dedication, and capacity to evolve—often plays a significant part in success.

Eric Cheng opened Sun Wah BBQ in Chicago in 1987, and his children grew up translating for English-speaking customers and witnessing how their father built Sun Wah into a beloved community restaurant. As they approached adulthood, Eric encouraged them to consider how their professional aspirations might play out there. “I spent 35 years making this business,” he’d explained. “Maybe you can make it bigger or make it last longer. Or you can come out of school, looking for a way.”

The maybe worked. In 2008, three of four siblings joined as co-owners: Kelly as general manager with a business degree, Laura as executive chef with a culinary degree, and Michael as barbecue master with hands-on education in the extremely physical cooking style that few chefs undertake today. A year later, they expanded to a 240-seat space, four times larger than the original, and saw immediate growth in their customer base—their investments and education paid off. At the start of the pandemic, Eric might have retired and permanently closed if working alone. His children chose to charge forward.

“He spent $100,000 for my undergrad and MBA, and I learned five words: ‘Niche market. Word of mouth,’” Kelly jokes about how her education reinforced lessons her grandfather had pressed into her father. “If we’re not a ‘family restaurant,’ we don't fulfill any of those five words,” she says. “On the back end, if my siblings were not family, we’d have quit on him or killed each other already.”

Such is the double-edged sword of working family relationships.

The John Zaragoza Family of Birrieria Zaragoza in Chicago

After leaving his corporate job, John Zaragoza opened Birrieria Zaragoza in 2007 with a dream of introducing Chicago to goat birria from his native La Barca, Jalisco. His wife, Norma, joined as manager a year later. Their four then-teenagers took on manual labor they couldn’t afford to hire out, swapping allowance for earnings. Today, daughter Andie manages. After years of working in other restaurants, son Jonathan joined as executive chef in 2017. (Erik, their youngest, works in the dental industry but occasionally jumps on the line or serves tables.)

Upon taking up the culinary reins, Jonathan established a POS system and scaled recipes to ensure consistency. John, on the other hand, prefers to make things up as he goes along. “I come in with a nurturing side,” says Norma, who helps smooth over clashes and walk-outs. “We need to stay together as a family and balance things out.” In turn, John praises his son’s industry insight. Jonathan values his parents’ HR expertise and the systems they’ve established that much larger companies outsource.

What started as his father’s passion project is now a successful 16-seat restaurant with a clear culinary identity that allows for creativity and flexibility. “To tell you there’s no plan to keep it going would be irresponsible,” Jonathan says of his focus on long-term sustainability and his parents’ eventual retirement. “I’m looking forward to the day where I can fire them both—that’s why we do what we do, not only in restaurants, but in life.”

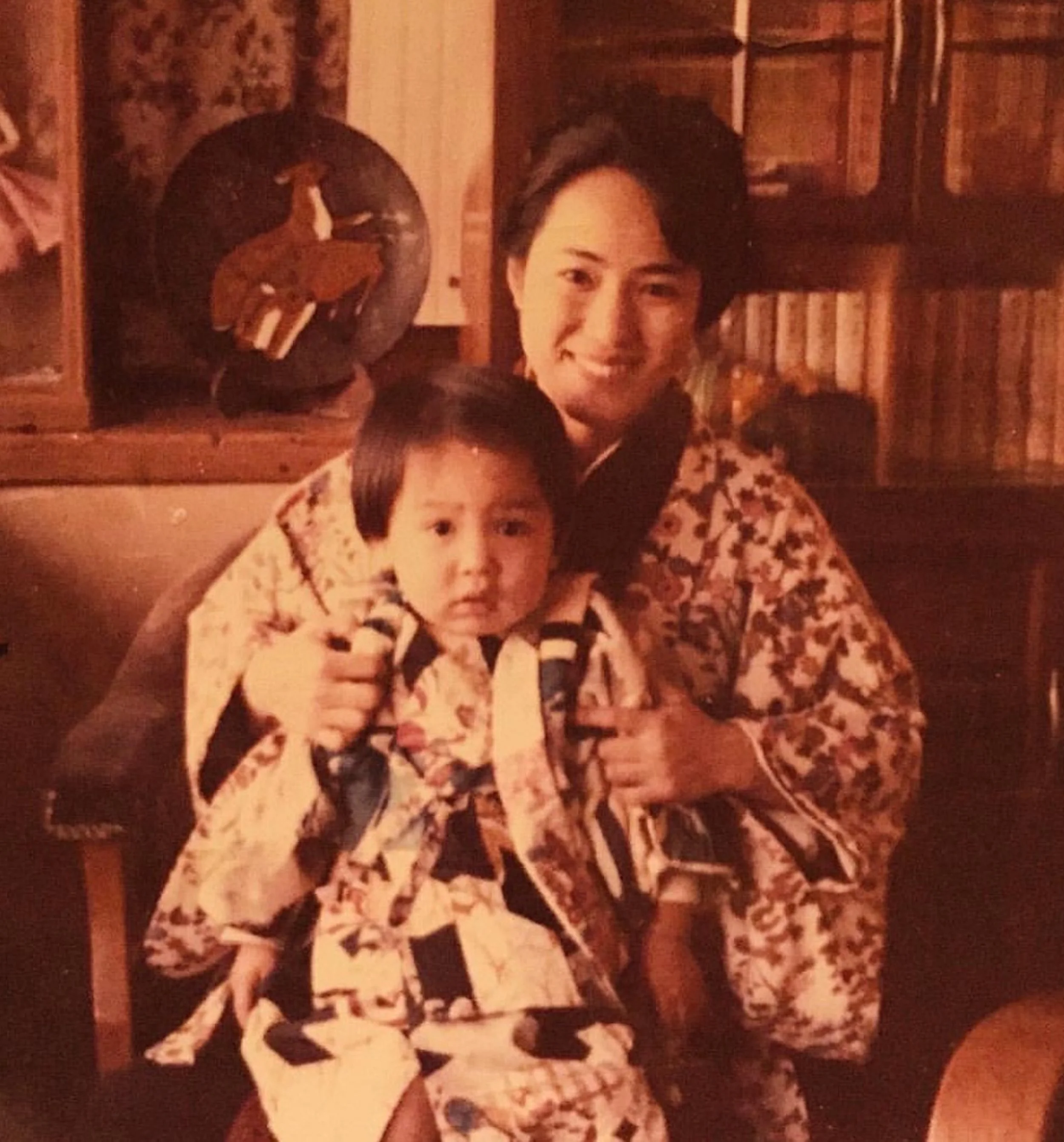

Bun Lai as a baby and his mother Yoshiko Lai of Miya's Restaurant in New Haven, CT

Conversely, Yoshiko Lai supported her son Bun’s decision to intentionally close their restaurant at the end of 2020—an idea he presented in 2019. “Maybe 99 percent of people would get angry,” Yoshiko recognizes. “But I thought he’d done enough.”

Yoshiko opened Miya’s Sushi in 1982 as New Haven, Conn.’s first sushi restaurant. It grew with such early success that she put her three children through celebrated private schools. “Nothing about the restaurant business was dazzling,” says Bun, who remembers watching his single mother haggle with vendors in broken English, cook every day, and manage the 100-seat space. “It was just hard work that she didn’t get respect for.”

He never expected to follow in her footsteps but, after firing an abusive sushi chef, found himself taking the job. After years of near financial ruin, Bun found his stride with the sustainable sushi practices that again put Miya’s on the map.

Yoshiko had taught her children that helping others was a noble aspiration—feeding regulars and New Haven’s homeless with an equally warm welcome was more important than seeking wealth or success. “I tell my children that we might lose business because of money, but god gave us what we need to survive,” she says. The family are active fishers, farmers, and foragers. They make business decisions on both practicality and spiritual guidance. So rather than sell Miya’s and monetize on sentimentality, Bun closed their building and transferred dining and educational experiences to his farm. “This was the best time to close,” Yoshiko says of her son’s instincts. “The whole universe was closing.”

Vishakha and Ankoor didn’t want their parents to stay open during the pandemic. “Any chef and GM will understand that our parents wake up and go to sleep thinking about Besharam,” Vishakha says. “Ankoor and I think about our parents.” But they recognize the preciousness of their mother pursuing her dreams now, especially during trying times. “The dreams and ambitions of my mother are so wide, I don’t think the three of us fully understand how wide they are,” Ankoor says. “I'm sure when she gets her first Michelin star, she'll be thinking about her second,” Vishakha adds. “Maybe she’ll rest then. Maybe.”

Cook from this article!

Beef and Pork Albondigas in Chipotle Peanut Sauce by Jonathan Zaragoza of Birrieria Zaragoza, Chicago