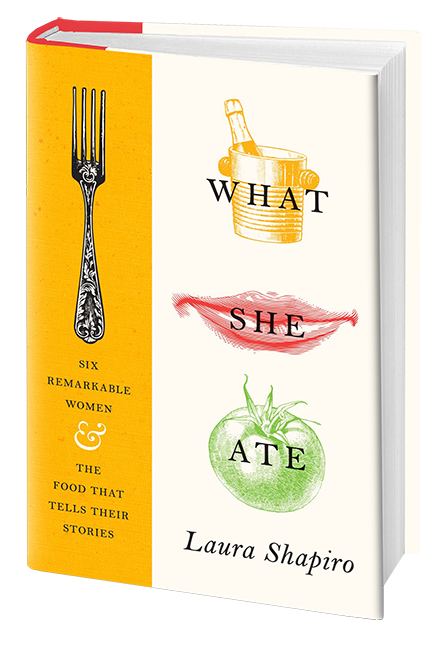

What She Ate by Laura Shapiro

Before I became obsessed with penning stories behind those who make food, I was obsessed with slipping into the souls of other peoples’ stories in body.

As a child, I "played Pocahontas", running through the back woods of my Connecticut home as silently as possible, and attempting to make 'clay pots' from mud. To this day, I hug trees, collect medicinal herbs, and shed tears when a hawk circles overhead – habits from the make believe world that got my nose first into books about Native American folklore and then, later, history. In High School, I fell deeply in love with Shakespeare. The power of presenting Juliet’s mock-suicide monologue to an audience vaulted me into a decade of stage performance as a career: I slipped into the soul of Bird – a high-wire performer who lost her husband to gravity and prepared to walk in Thin Air again only two days later – strangled a man with my lavender stockings as a 1960’s murderess for hire in London, and rekindled my loveless marriage on the Italian Riviera amidst the roar of the 1920s.

When my real physical body was no longer strong enough to perform because of illness, I stopped telling stories on a stage and practiced telling stories on a page.

Reading Laura Shapiro’s What She Ate felt like slipping bodily into souls again.

On sale now, What She Ate focuses on Six Remarkable Women and the Food that Tells Their Stories.

“Every life has a food story, and every food story is unique,” Shapiro asserts in her introduction.

“Tell me what you eat!” she begs of the women in her research... “But I wanted to know everything else, too."

Did they eat alone or with others? Did they taste the flavors in their food or eat quickly past them? Did they ever feel true hunger, or did they often overspend at the market?

Eight pages in and I’m already beyond curious. But do these stories – only six of them? – work together as a book? In a world where I'm constantly reminded that clicks and brevity are fanatically given valued above rich storytelling, and food publishing reserved for recipes and celebrity, will this indescribable collection of odd chapters make sense in my hand?

Because upon first glance this book is... different. The six chapters are uneven in length. They read somewhere between "short story" and, were they fiction, novelette. Shapiro states she chose six specific women with gray areas in their published history that left questions for her to answer. That the gaps in what we know of them might be better understood through what that did -- or did not -- eat.

And yes! It is somewhat easier to comprehend Eva Braun’s unflappable loyalty to Hitler after absorbing her youthful romantic obsession with him, and how he filled and her bottomless materialism with gowns, rigid dieting, and thrice-daily champagne. Eleanor Roosevelt reads as a heroine for betrayed wives everywhere when she takes revenge via stuffed eggs and “watery prune pudding” served at White House dinners.

Yes, their food stories fill in gaps. But even more than the delicate onion-skin unfolding around their insular food stories, soul-slipping happens because of Shapiro's skill with the “everything else, too”.

Braun’s obsession with her figure and what she ate to maintain it strikes a suffocating portrait defined against a backdrop of European famine and German feast. Eleanor might be looked at as a bitter, prudish matron had Shaprio not given us such ample time to grow with her into First Lady, advocate, and then widow.

They are my Juliet pondering suicide against fear of waking in "an ancient receptacle where for these many hundred years the bones of all my buried ancestors are packed." They are Bird on a wire, shaking above sixty feet of air with no net to catch her.

These chapters work as a book because each is rich in story. And they work because Shapiro uses craftily sharp storytelling, like a good English white sauce with plenty of lemon. Each story is devoted to the big picture, like Dorothy Wordsworth's lifelong devotion to her brother, William. They’re best read slowly, "savored" like Helen Gurley Brown’s “fake” recipes.

Fittingly, Shapiro’s inscription – For Jack – quotes the Bard: “How many things by season seasoned are.” The Merchant of Venice brings me back, too, to presenting that play against a sunset bouncing off the Long Island Sound.

What She Ate will bring you somewhere, too.

Have fun slipping into souls.